Jam Gallahue just hasn’t been able to recover from the death of her boyfriend Reeve Maxfield. “I loved him,” she explains, “and then he died, and almost a year passed and no one knew what to do with me.” As a last resort, Jam’s parents send her to The Wooden Barn, “a boarding school for ’emotionally fragile, highly intelligent’ teenagers.”

Jam Gallahue just hasn’t been able to recover from the death of her boyfriend Reeve Maxfield. “I loved him,” she explains, “and then he died, and almost a year passed and no one knew what to do with me.” As a last resort, Jam’s parents send her to The Wooden Barn, “a boarding school for ’emotionally fragile, highly intelligent’ teenagers.”

Meg Wolitzer’s YA novel Belzhar follows Jam on her journey of recovery, although it probably won’t be the sort of recovery readers will be expecting.

Jam is picked to take a course called Special Topics in English, the “smallest, most elite class in the entire school.” Taught by Mrs. Quenell, Special Topics has a reputation at The Wooden Barn. Jam’s roommate, DJ, tells her that students who haven taken the class act like it’s no big deal, but “when it’s over, they say things about how it changed their lives.”

Jam shares the class with Casey, a girl in a wheelchair, Sierra, Marc, and Griffin, a boy who is “good-looking but in a hostile way.” Their special topic is Sylvia Plath, who will be the only author the five students will study. In addition, they are required to write in journals that Mrs. Quenell hands out to them. Mrs. Quenell tells the students that each of them “has something to say. But not everyone can bear to say it. Your job is to find a way.”

The thing about these five students is that they have each suffered some sort of trauma and it turns out that their journals and the entries they write in them magically transport them back to a happier time in their lives. These experiences, which they call going to Belzhar (a weird take onthe title of Plath’s only novel The Bell Jar) causes them to open up to each other and to the world.

Whether you buy into the magical realism elements of this novel or not, there is certainly truth to the fact that some people get stuck in their grief or anger. Each of these teens has been trapped by their experiences and the act of writing allows some of the poison in their lives to seep out. “Words matter,” Mrs. Quenell tells her students, and I wholeheartedly agree.

Not everyone will appreciate Belzhar. I can see how some students might balk at the notion of Belzhar as a real place, but as a metaphor it most certainly works. Human beings do get stuck. We hold on to things and people that are not healthy. We don’t fully live; we deceive ourselves. It takes work, sometimes, to shed trauma, but surely it’s worth it.

“You’re all equipped for the world, for adulthood, in a way that most people aren’t…So many people don’t even know what hits them when they grow up. They feel clobbered over the head the minute the first thing goes wrong, and they spend the rest of their lives trying to avoid pain at all costs. But you all know that avoiding pain is impossible.

Belzhar is worth a look.

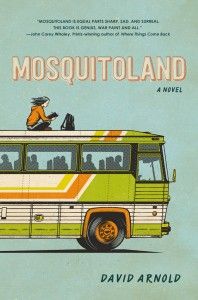

late: her parents’ divorce; her father’s quicky marriage to Kathy; their subsequent move from Ashland, Ohio to Jackson, Mississippi. When Mim overhears her father and stepmother talking to the principal, she’s convinced that her biological mother is sick and makes the decision to hop a Greyhound and travel the 947 miles back to Ohio to see her.

late: her parents’ divorce; her father’s quicky marriage to Kathy; their subsequent move from Ashland, Ohio to Jackson, Mississippi. When Mim overhears her father and stepmother talking to the principal, she’s convinced that her biological mother is sick and makes the decision to hop a Greyhound and travel the 947 miles back to Ohio to see her. Gah! This book, you guys.

Gah! This book, you guys. Becky Albertalli’s YA novel Simon vs. The Homo Sapiens Agenda won the William C. Morris Debut Award, but the accolades don’t stop there. The book has been praised or recognized by everyone from ALA, Carnegie, Oprah and Lambda. Although this book has been on my shelf for a couple years, as soon as I knew the movie was coming out – I knew I had to read it…and I am soooo sorry I waited so long.

Becky Albertalli’s YA novel Simon vs. The Homo Sapiens Agenda won the William C. Morris Debut Award, but the accolades don’t stop there. The book has been praised or recognized by everyone from ALA, Carnegie, Oprah and Lambda. Although this book has been on my shelf for a couple years, as soon as I knew the movie was coming out – I knew I had to read it…and I am soooo sorry I waited so long. Courtney Summers is one of my favourite YA writers. Cracked Up to Be was her debut novel, but it’s the fourth book I have read by this talented Canadian author. I have also read her terrific zombie novel

Courtney Summers is one of my favourite YA writers. Cracked Up to Be was her debut novel, but it’s the fourth book I have read by this talented Canadian author. I have also read her terrific zombie novel  Jocelyn’s twin brother Jack is dead. At least that’s what she thinks until she receives a letter from him that sends her on a wild chase. First stop: Noah Collier.

Jocelyn’s twin brother Jack is dead. At least that’s what she thinks until she receives a letter from him that sends her on a wild chase. First stop: Noah Collier. A couple years ago I read Ruta Sepetys’ novel

A couple years ago I read Ruta Sepetys’ novel  Who doesn’t love a good scare? Not Ivy Jensen. That’s not her fault, though. When she was 12, someone broke into her house and slaughtered her parents. In her recurring nightmare about that horrible night, Ivy wakes “with a gasp, covered in [her] own blood. It’s everywhere. Soaking into the bed covers, splattered against the wall, running through the cracks in the hardwood floor, and dripping over [her] fingers and hands.”

Who doesn’t love a good scare? Not Ivy Jensen. That’s not her fault, though. When she was 12, someone broke into her house and slaughtered her parents. In her recurring nightmare about that horrible night, Ivy wakes “with a gasp, covered in [her] own blood. It’s everywhere. Soaking into the bed covers, splattered against the wall, running through the cracks in the hardwood floor, and dripping over [her] fingers and hands.” Pam Smy’s lovely hybrid novel tells the story (in words) of Mary and (in pictures) Ella – two girls separated by twenty-five years. Ella and her father have moved into a house that looks out onto Thornhill Institute which was “established in the 1830s as an

Pam Smy’s lovely hybrid novel tells the story (in words) of Mary and (in pictures) Ella – two girls separated by twenty-five years. Ella and her father have moved into a house that looks out onto Thornhill Institute which was “established in the 1830s as an  orphanage for girls” and sold in 1982 “after the tragic death of one of the last residents, Mary Baines.” For the last twenty-five years, the house has remained vacant, although plans have been made to develop the site.

orphanage for girls” and sold in 1982 “after the tragic death of one of the last residents, Mary Baines.” For the last twenty-five years, the house has remained vacant, although plans have been made to develop the site. In the present day, Ella spends much of her time alone, too. Her father, who clearly seems to love her, is away a lot. Her mother is presumably dead. Ella is curious about the house she can see from her bedroom window and the girl she sometimes glimpses in the overgrown garden behind the walls

In the present day, Ella spends much of her time alone, too. Her father, who clearly seems to love her, is away a lot. Her mother is presumably dead. Ella is curious about the house she can see from her bedroom window and the girl she sometimes glimpses in the overgrown garden behind the walls is a celebrated graphic novelist, whose series Diana: Queen of Two Worlds, tells the story of “a suburban girl who lives with her “painfully average” family which includes her high-strung easily overwhelmed mother, her ineffectual father, and her dull-witted, staring lump of a sister.”

is a celebrated graphic novelist, whose series Diana: Queen of Two Worlds, tells the story of “a suburban girl who lives with her “painfully average” family which includes her high-strung easily overwhelmed mother, her ineffectual father, and her dull-witted, staring lump of a sister.”